Diving Into The Data

By joe | February 15, 2018

A November 2017 survey from Blackbook Market Research shows that only 3 percent of long-term care facilities have the capabilities for data assessment. Although more senior living communities are adopting electronic health records, it’s the ability to use the data to have an impact now that’s a challenge.

Presbyterian Senior Living is in the early stages of collecting and merging data with its mission of person-centered solutions to guide the care of its residents on a case-by-case basis. The Dillsburg, PA-based not-for-profit organization has retirement and senior care services in 30 locations across four states.

Dr. Steven Fuller, vp and corporate medical director at Presbyterian Senior Living, is driving its data collection and analysis—tracking readmission rates, fall rates, infections, pharmacy data and X-ray data to ultimately improve staff performance, better allocate resources and create better health outcomes.

“Data allows a lot of insights that we wouldn’t have without it,” said Fuller. “First consideration is the person-centered part of it and caring for individual residents, making sure we’re creating the safest environment for them. But in order to accomplish that we need to expand our view beyond the individual resident and use a population health approach not only within a community but across our corporation.”

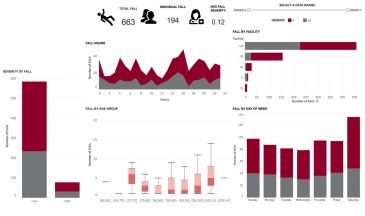

Falls, for example, on a preliminary view, often appear in an isolated group of rooms—a resident’s room, dining room, hallway and other locations. There may be vulnerable days in the week or falls scattered throughout the week.

“Data really guides us in our investigation of specific underlying causes of falls, which more likely will lead us to identify underlying factors that we can change to improve our overall performance,” said Fuller. “Without this, we wouldn’t be able to have focused and targeted, very specific conversations that enable us to see what we do have in place and how to improve in order to address vulnerable periods, investigate the differences between communities or whatever we’re looking at.”

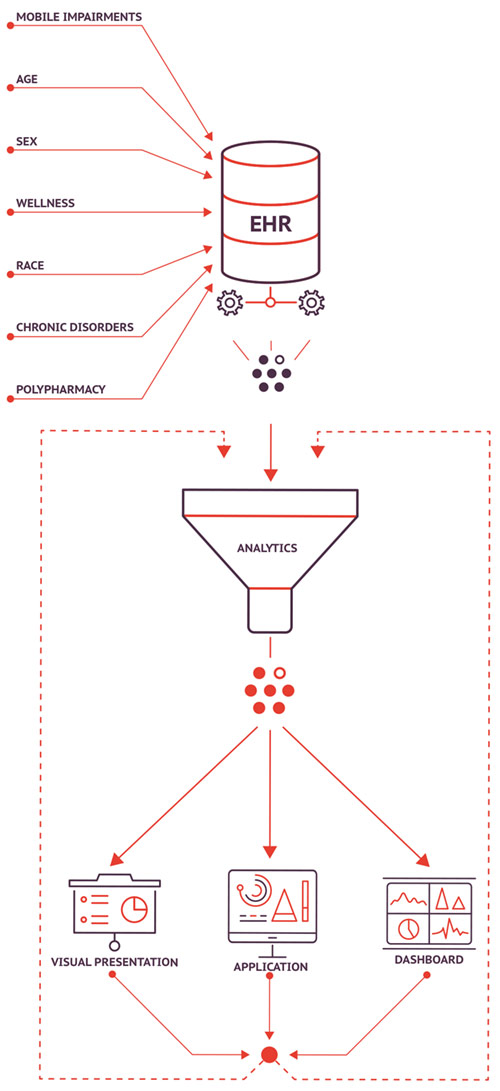

Nurses and aides document falls in the electronic health records (EHR). Fuller aggregates that data to another data base, then pushes it through analytics he developed to look at why falls are occurring in specific rooms or areas such as short-term, long-term or memory care. Or physical characteristics such as rooms that are cluttered with oversized furniture blocking the pathway from bed to bathroom, or positioned for easy navigation.

“It’s dynamic, a moving target. The data allows us to track all this and get specific about identifying trends,” said Fuller. “The ‘aha’ is not so much in the ultimate findings, because it’s still so early, but it’s the initial look into our data. It’s like opening a book or walking through a door and saying, ‘Look at this picture and discovering the treasure that’s inside the data, the stories that are there.’ The data allows us to understand the story of each community more than we could otherwise.”

Meth-Wick Community CEO Robin Mixdorf agrees with Fuller’s analogy, saying, “I’m so intrigued and excited by the opportunity to take real life experiences and data and see if we can’t make life better.”

Also in the early stages of using its data for fall analysis and prevention, the Cedar Rapids, IA, Life Plan Community was already focused on being a wellness campus helping people live their definition of their best possible life. The majority of residents lives independently, but there’s also assisted living both for supportive services and dementia, a nursing facility that includes a neighborhood licensed for chronic confusion and dementing illness, and home health.

The campus began collecting falls data several years ago, understanding fear of falling alone substantially changes the quality of a person’s life, often resulting in isolation.

Data came in a number of ways besides EHRs, including balance, stability and stance information from the wellness department’s Bio Dex equipment and the WelTracs questionnaire completed when the successful aging coordinator visits each new resident.

“When we started encouraging self reporting among those living independently, obviously the number of falls on campus skyrocketed,” said Mixdorf. “But then we could do a root cause and anecdotal analysis. We had incredible data—day of the week and time of the day residents fell, whether they fell getting up from a chair or walked five steps or when getting out of bed. But we had no time to put it together in some kind of a system or staff expertise to create the tool that was needed.”

The community had a falls committee meeting bi-weekly looking at trends and patterns, but trying to get data also took away time to understand what’s really going on, plan and strategize solutions and interventions.

That’s when Mixdorf reached out to WildFig, a data, science and analytics consultancy. She wanted things like data mining in the anecdotal analysis, what words keep coming up, good tracking and dashboards created.

“It took collaboration with WildFig to draw pictures so we could step back and look at specific data to determine if we have the right staffing in that area, the right floor coverings, the right lighting. Do we have people attending balance classes who should be attending or if they decline balance classes, what’s the advent of them falling?

“Quite frankly, without the tool, it’s just bits and pieces. We knew we needed to do something. We knew we could collect the data. Now we’re in the stage of what can the data give us,” said Mixdorf.

The “tool” came in the form of three outputs, according to WildFig Chief Scientist Kevin Purcell, Ph.D.—first, a centralized dashboard that the falls committee could use to see what’s happening currently with falls occurring and a series of dashboards to have at their fingertips at meetings; second, an interactive computer model allowing them to punch in information about a current or prospective resident, and based on what’s going on, get a probability of a fall risk.

“The third was more of a research output,” said Purcell. “We gave them back an analysis of some of the trends, patterns and causal relationships in falls in their community, and we able to relate the odds and risks of falling in their community to the public at large. Data science is really about finding new interesting resources, how to find data and capture its untapped potential.”

John Bassounas, WildFig president/partner, emphasized that a lot of the firm’s work is upfront, getting the data needed—something he predicts will be more accessible in the future as residents become more data-engaged due to advancing technology. He also believes data is a way to build a bridge not only between provider and resident, but also the family wanting a link to their loved ones.

John Bassounas, WildFig president/partner, emphasized that a lot of the firm’s work is upfront, getting the data needed—something he predicts will be more accessible in the future as residents become more data-engaged due to advancing technology. He also believes data is a way to build a bridge not only between provider and resident, but also the family wanting a link to their loved ones.

“We’re finding that many aging services providers are data rich, but just insight poor at times. Our charge is to help pull insights out of that valuable data, identify gaps where they can collect more,” Bassounas said. “We provide suggestions around standard operating procedures in areas where a community can improve to be sure that the data is being input cleanly, effectively and consistently. The better the data, the more powerful our models can be, the better outcomes can be.”